Besides tea-shops and gardens, the project I am really excited about at the moment is the archive. The

Library is out of bounds at the moment, at risk from falling ceilings due to

all the rain we had over winter - the poor castle can't absorb any more. But the archive materials are available, and I

have been diligently (well, sometimes) going through boxes, listing details properly

so that there is some kind of systematic information available.

I wasn't only motivated to do this by curiosity - although of course

I am curious. It's more to do with my own writing as well (besides the strange need, common to many academics and students, to feel closer to those who are gone, even if we never knew them, to read their words and learn about their lives). I try to imagine the lives of those who built

this place, for whom it was a kind of home, a different kind of home to

"normal", but imagination isn't enough. I need to know more, be more accurate in what I write,

not just fantasise about the past. Unlike

many people who wrote about the Bulloughs in the 1970s and 1980s, for example (these

magazine articles keep turning up in the archives, usually full of inaccuracies

and myths), I bear no resentment towards them for their wealth; instead I feel

somehow fiercely protective, perhaps because out of all the experiences on this

island so far, living in their castle - a privilege I could never have expected

in my life - has been the most enduring, positive and lovable. It has felt safe, even homely, at times when I

have felt lonely and unhappy. No matter

that I would never have fitted into their world. I'm not of their time, so our respective

"classes" have no real meaning - not now. Instead, gifted with a life a century on (I

am 101 years younger than George, who was born in 1870), I have experienced the

joys and challenges of an education that women in those days could never have

had. When you are lucky enough to have

an education and your (comparative) freedom (I don't have to skivvy for a

living), you get a sense of being equal with anyone. You feel you are outside "systems" -

class systems, gender systems, or perhaps a better word is "hierarchies"

- even though the first thing you learn as an academic is that this is an

illusion - no-one is outside their own history. But despite the illusion, it's still true that

education can give you a freedom in your mind that you may not have in terms of

money. Your mind is your most important birthright,

not your wealth, status or family. In

this way, being an archivist becomes not just a privilege where you are allowed

to see into other people's lives - it can become a way of finding a common

ground with people who, had you been born into their time, would hardly have

known what to say to you.

Anyway I am digressing from the important thing, which is the archive

itself. And what have I learnt so far?

So far I have mainly been looking at letters. Not personal letters or love letters, I'm afraid.

But these letters are just as

fascinating. They describe how the

Bulloughs lived their everyday lives, how they shaped their island and their

castle, the networks of people they needed to fulfil their dreams. For example, a fishery to provide salmon and sea-trout eggs, to build

fishing grounds at Long Loch - where there are still trout, as we explained to

our visitors last week, but no salmon. And

now we know why.

After an initial set-back, where it appears that buying fish eggs is

going to prove too expensive, it seems that Sir George and his factor finally

reach an agreement with the fishery in 1928. Exacting and complicated arrangements are made

between the factor on Rum, R. Wallace Brebner, and his contact at the Solway

Fishery, J.G. Richmond, for the transportation of salmon and sea trout ova in

special boxes, by train and boat, to be accompanied by the gamekeeper, McNaughton,

early in 1929. A risky business, as the

eggs won't survive if they are subject to too strenuous conditions; they must

be kept "cold, but above freezing point".

|

| Influenza strikes |

But disaster nearly strikes as McNaughton

falls ill of flu in Glasgow and can't get to Mallaig. Worried letters are exchanged, Richmond

sending telegrams and letters sometimes simultaneously to ensure his

instructions, as well as the eggs, arrive safely. In his fine, copper-plate handwriting, or in careful typewriting, he

describes the conditions needed and what to do with the hatching boxes once

they finally arrive at Rum (or Rhum, as it was known at George Bullough's request). Later, we learn that the salmon do not do at

all well and even the sea trout eggs do not hatch as quickly as hoped. It's all down to the weather (what else on

Rum?); Richmond writes he has never known of such a prolonged cold spell

Shipping live creatures to Rhum did not stop at fish eggs, or indeed,

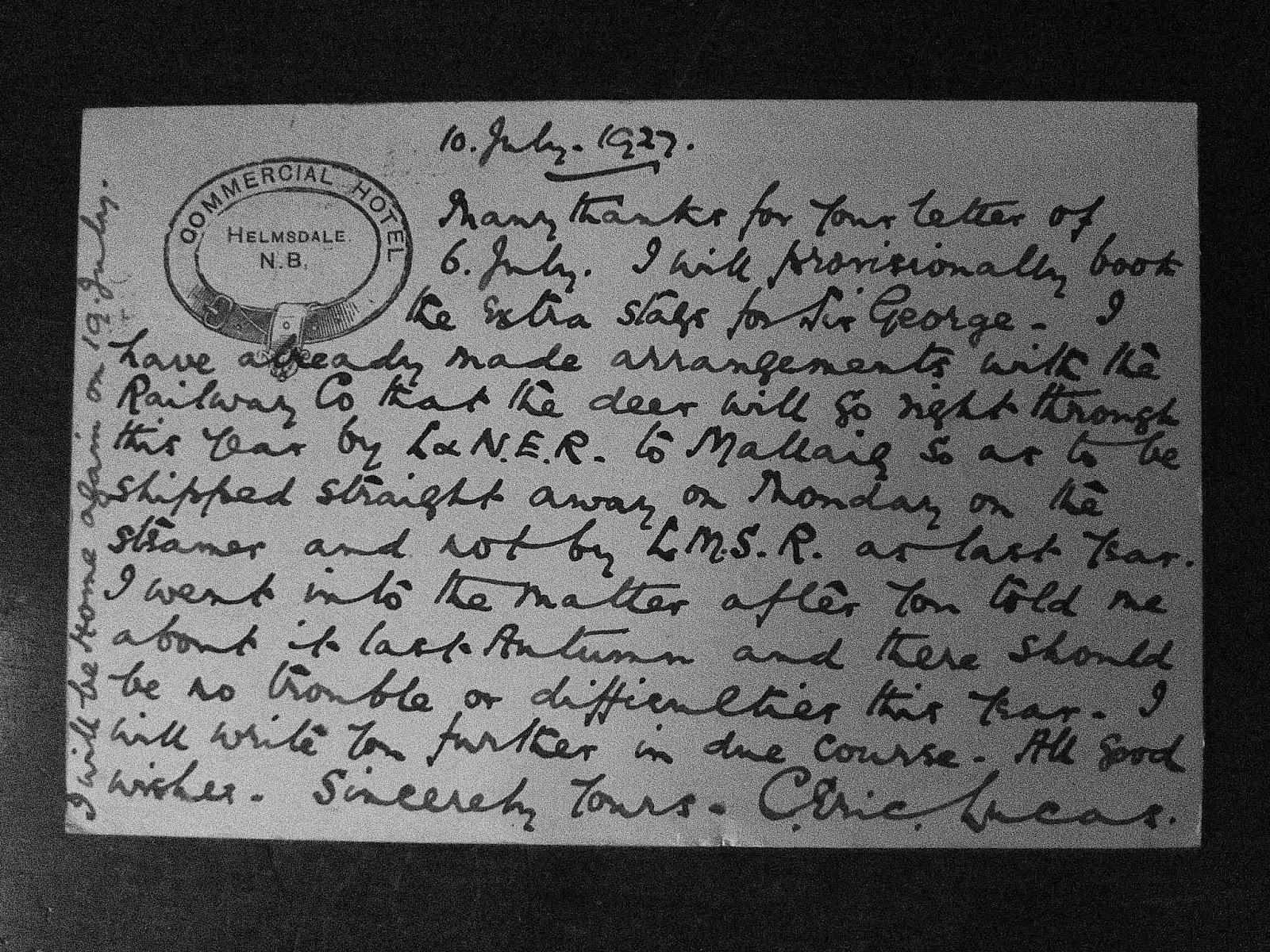

as we know, alligators. Two small

postcards from a C. Eric Lucas from consecutive years (1927 and 1928) note that

"the stags for Sir George" will be sent direct to Mallaig by the

London & North Eastern Railway, not

the London Midland and Southern Railway as they were last year; it is hoped

that this will avoid the problems experienced with the LMSR (what problems? Did

the deer escape? Were they travelling on

the wrong ticket?). I at first thought

this must mean venison, but the second postcard clarifies that live deer are

meant: "the best plan will be to mark the six Hinds for Sir George by

taking the top off the left Ear. It is as good a distinguishing mark as is

possible." Evidently, there was a whole trainload of deer on their way to

the Highlands, destined for the hills and perhaps later, the hunter's pot.

Many of the letters are about money, of course; insurance and tax

play a major part in the correspondence. Both George and Monica take a keen interest in

the policies and we learn that in the 1920s they kept not only two Trojan cars,

but also an Albion and a "Motor Lorry", all of which need insuring. Meanwhile their solicitors are determined to

make their accounts as correct as possible and chase up receipts, valuations

and expenditure; we learn that they require proof of how much the estate spends

on hens' eggs (£2 15s), but the proof is not forthcoming. Brebner writes, somewhat tetchily, that their supplier,

MacLeod simply refuses to provide receipts: "He is supplying the eggs but

no matter how often asked for will never send acknowledgment of payment,

treating all business as cash transaction." Instead Brebner is forced to

request a copy of his own cheque from the Bank, which is then forwarded to the

solicitors.

I learn too of how the new boiler and heating arrangements were

ordered and obtained, how kitchen ranges were scrutinised and finally built (in

the 1920s, not as early as I expected), and read the original letter of

application sent in 1914 by the gamekeeper, Duncan McNaughton, who remained on

the island for many years and later became factor after Brebner was sacked. "Dear Sirs, seeing you are advertising for a

Gamekeeper Stalker in Sat's Scotsman I apply for same. I am 27 Years old

Married, w[ith] family I may say I thoroughly understand Pheasant rearing

Grouse and Partridge Driving the breaking and working of mostly all sporting

dogs 11 years experience in dogs and the management of a Grouse Moor & of

which I had experience in Deer stalking and Driving on the strathgartney [sic]

Deer forest and Grouse moor where the killed annualy [sic] 20 stags. I am strictly sober (and good pipes) You can

have my character by writing to Mr John Paterson, Brenachoile Lodge, Trossachs,

Callands, and A.S. Maenaghten, Craiginie, Balquhidden, Perth Shire and T.H. Mann

Esq., Trulls Hatch, Bothesfield, Sussex.

I am Yours Obediently Duncan McNaughton".

I've yet to learn what happened next - during the war, and the flourishing 1920s

(although, by all accounts, not as flourishing as the Edwardian years). We always think of the Bulloughs as Edwardian,

but of course they were far more than that; Monica lived through nearly a

century herself.

Meanwhile, we continue to establish ourselves in our own small way;

sadly we have no classic cars (nor would the roads let us drive them if we

had), but we have our little vegetable plot. We don't aim to be self-sufficient, not

physically - what I want from my time here is to learn to be mentally

self-sufficient, but also to learn when and how to need others. A writer in West Word last month spoke about

how in a truly healthy society we would know that we are all dependent on each

other, rather than striving for total independence from other people. People with lots of money can easily become

isolated, not part of the social fabric, as well as people who have none,

because they can view themselves as not needing anyone or anything, and

conversely, not needing to give anything back either. Sometimes

I feel we're so much less advanced than George and Monica - our society here is

at such a basic level. Other times, I

feel we're ahead of them in our striving to each contribute what we can. I'm glad we have the opportunity, as it were,

to live alongside each other, past and present.

|

| Hope in our garden - an onion is growing... |

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.